Composer & Milwaukee native Emily Cooley returns to meet with area students

David Lewellen

PUBLISHED

Tagged Under: 2017.18 Season, Conversations with Composers, Guest Artist

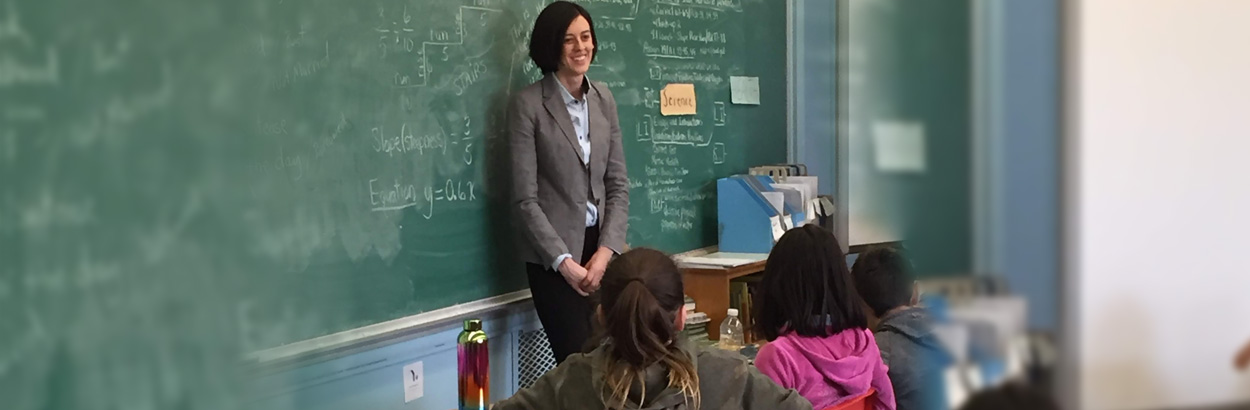

Watching 28-year-old composer Emily Cooley interact with a room full of sixth-graders proves that the hierarchy of genres has disappeared.

Cooley, a Milwaukee native, is one of nine living American composers on the Milwaukee Symphony’s subscription program lineup this year. The orchestra will perform her piece “Green Go to Me” in March, but students got a preview of it earlier this year during daytime educational concerts.

Visiting Trowbridge Street School, an MPS elementary school in Milwaukee’s Bay View neighborhood, Cooley talks briefly about the piece which the class of 30 sixth-graders — all races and colors, and mostly low-income — will hear the next day at the Marcus Center. She describes how she tries to imitate the sounds of nature in the orchestra, and how the waves of sound build. Then she asks the fateful words, “Any questions?”

And the torrent commences.

How much school do you need to be a composer? She had four years of college and four years of graduate school, but “anyone who writes music is a composer.”

How long does it take to compose a piece? “It depends on the length of the piece and how many instruments are playing.” For this particular seven-minute piece for full orchestra, two months of daily work.

What instruments does she play? Mostly piano. What’s her favorite piano piece? “I don’t take lessons anymore, but when I did, I liked Chopin. He’s a Polish-French composer from the 1830s. And Debussy, another French composer.”

Could she write a piece for kids their age? “That’s definitely something I want to do.”

What’s her favorite piece that she’s written? “Argo, another piece I wrote for full orchestra, because it turned out the way I wanted it to. That may seem like a strange thing to say, but when composers note things down on the page, you don’t know how it’s going to sound.”

Has she ever been ashamed or sad when she heard her music performed? “That’s definitely happened. Sometimes I’ve written music that’s too hard to play, or I wrote something that I thought would sound great, and it didn’t.”

How much money do composers earn? “It depends” (as the adults in the room laugh nervously). “Most composers have to do other jobs to get by. I earn about half my money from composing, and I also teach.”

What genre does she write? “It could be called new music, but that’s really broad. Or contemporary classical. It could be anything. The only thing that ties it together is that it’s written down.”

What other genres does she listen to? Pop and rock. What about rap? Does she like Young Thug? “I’m not a fan, but I’ve heard some of it.” Who’s her favorite rapper? Kendrick Lamar – a response that draws some “ooohs” from the class.

“I didn’t know what sixth-graders listen to, but now I do,” Cooley says with a laugh an hour later, in the more tranquil setting of the Intercontinental Hotel. But it’s not all that different from what she and other composers of her generation have absorbed. “I don’t see a hierarchy of genres,” she continues. “What I do is no more sophisticated than any other genre. Being written down is the only real distinction I’ve been able to think of.”

But that kind of creative cross-fertilization has had a hard time making it into the institutional setting of the symphony orchestra; the MSO’s commitment to living composers this year is unusual. “There is that conflict, between fundraising and new work and the younger audience that institutions have to figure out how to deal with,” Cooley said. “It really follows a pattern – a new 10-minute piece, a concerto, intermission, symphony. I get paired with Tchaikovsky a lot.” Told that in March she’ll actually be paired with Prokofiev here, she laughs; it proves the point. “We all have to be willing to take risks and get out of that model.”

To help herself get out of that model, Cooley teaches composition regularly at a maximum-security prison near her home in Philadelphia, which exposes her to “people who have a lot of interesting things to say that we don’t usually hear.” It also makes her aware of the advantages she had from University School, Yale, and Curtis in pursuing a classical career. “But so many genres are just taught by exposure,” she says. “It’s how much you put into it and how much you absorb.”