Bernstein Connections

DAVID LEWELLEN

PUBLISHED

Tagged Under: 2017.18 Season, Bernstein Festival, Classics, MSO Musicians

What if Leonard Bernstein were the Milwaukee Symphony’s music director?

The world will actually celebrate the great American composer and conductor’s 100th birthday next year – but in the absence of a music director for the coming season, the MSO imagined what Bernstein might have liked to program. And at least three people associated with the orchestra have personal memories to draw on.

Executive Director Mark Niehaus, who played trumpet under Bernstein in two youth orchestras, pointed out that the 2017-18 classics season has at least one American work on every program, both from composers of the Bernstein-Copland-Gershwin generation and from many living composers, whom we would like to think Bernstein would have championed if he had lived longer. The season also includes plenty of work by Bernstein’s favorite composers to conduct, such as Beethoven, Mahler, and Britten.

Having Bernstein as a guest conductor when he was a teenager “was like having Hank Aaron or Babe Ruth to coach your baseball team,” Niehaus said. He remembered a spot in Schumann’s Symphony No. 2 that features a long, fast difficult passage for the first violins. Knowing that most young violinists would be scared of it, “Bernstein told them to stand up,” Niehaus said. “He said, ‘Play it like it’s a concerto. Own it.’ And as they played he walked through the section, smiling and encouraging them. And at the concert, those guys tore it up.”

When Niehaus was at Tanglewood, the summer home of the Boston Symphony that also hosts youth orchestras, he was in a car accident, and Bernstein came to see him in the hospital — a visit he doesn’t remember. But a year later, at the Pacific Music Festival in Japan, “Bernstein came to the rehearsal a little late, and instead of going to the podium, he came back to the trumpet section and gave me a hug and asked how I was doing.”

It’s quite a story, but Niehaus says, “He was one of those people that everyone felt they had a special relationship with him. And that’s possible. It’s kind of like Yo-Yo Ma now – everything revolved around him, but he also made it about everyone else.”

Principal clarinet Todd Levy played under Bernstein in the youth orchestra at Tanglewood, and a few years later while studying at Juilliard in New York City, he saw the composer waiting to cross the street at a red light. Levy reminded him of their previous meeting, “and he said, ‘Oh, of course I remember you!’ I don’t know if he really did, but he always made you feel like you were the most special person in the place.”

Some years later, Levy played under Bernstein again at the New World Symphony in Florida. “He wasn’t technically perfect,” Levy said, “but he got to the bottom of the emotion of the music. It’s hard to teach emotional depth to young players — you need that life experience. But that’s why he was a great teacher. One person’s experience can really transform the way people look at music-making.”

Bernstein’s famous gyrations on the podium were not for show, Levy said. Instead, “it was a reflection of how he felt the music was happening at the time. It was not at all contrived. He was trying to get people to play it the way he felt it.”

MSO concertmaster Frank Almond vividly remembers playing at Tanglewood when he was 15 and waiting for Bernstein to lead a rehearsal. “This giant car comes rolling across the lawn,” he said, “and he gets out, in a white suit, with an entourage. There’s an introduction and he makes a few jokes, and then — for the first time, I saw an orchestra transform into something really different. Everyone wanted to play their absolute best within 15 seconds. He really was larger than life. I remember that transformation really blew my mind. We’d never sounded that good.”

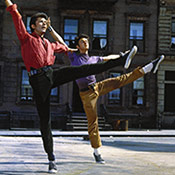

This season, Almond is excited that the MSO is performing what he sees as Bernstein’s two greatest works: West Side Story and the violin concerto Serenade after Plato’s Symposium. “He was known in his lifetime as a conductor, but he wanted a legacy as a composer,” Almond said. “He’s one of the few people who can truly be called a Renaissance man. He had abilities in so many different areas.”