There’s always something fresh to discover: Musicians of the MSO Reflect on Beethoven

David Lewellen

PUBLISHED

Tagged Under: 2019.20 Season, MSO Musicians

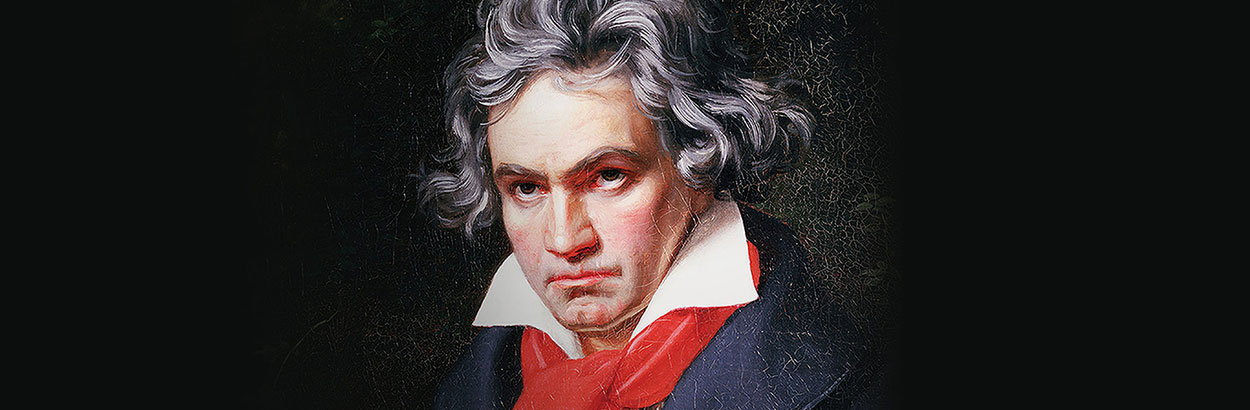

Schroeder from “Peanuts” isn’t the only person who celebrates Beethoven’s birthday. Over the next two years, the entire classical world will be gorging on all things Beethoven to mark the composer’s 250th year.

The Milwaukee Symphony is no exception. The 2019.20 season features the master’s first six symphonies, three piano concertos, and the violin concerto; the 2020.21 season will include more. It’s a good time to be a fan of Beethoven – and if that doesn’t include everyone, it’s close.

“It’s almost like asking why the Beatles are popular,” said associate principal cello emeritus Scott Tisdel. “Everyone loves the Beatles, because they are universal. Same with Beethoven. The idea of someone not liking Beethoven is preposterous.”

“I love Beethoven. A lot. Just do,” said second violinist Lisa Fuller. “Hard for me to explain why. Just like one can visit a forest or ocean over and over again, there’s always something new or different each time you visit. And each time you visit, you are different too. And you know that thrill of watching your kids experience things for the first time and reliving it through their eyes? Knowing that there are folks in the audience who may be hearing a work for the first time, there’s a real sense of purpose and mission when you remember that.”

Although Beethoven’s music is a staple of any orchestra’s season, musicians agree that there is always something to keep it fresh. “They are also endlessly challenging because there are many different ways to interpret them,” said associate concertmaster Jeanyi Kim. “For example, we have played Beethoven 5 countless times, but every conductor conducts the opening slightly differently.”

“I always want to play a Beethoven symphony as if it were my first time.” said principal bassoonist Catherine Chen. She has fond memories of the first time she ever played the Third Symphony, at age 18 with a student orchestra in Carnegie Hall. “A semi-obscure piece of his that I wish was performed more often is his Symphony No. 1, his least performed symphony. Luckily for me, the MSO is performing it on the upcoming Classics subscription.”

“I think what sets Beethoven apart is the sense in which you feel him pushing the envelope or testing the limits of traditional classical form for the sake of musical expression,” Kim said. “Dynamics became extreme, going from pianissimo to fortissimo at times; number, order, and inner construction of movements shifted from the norm; length, meter, phrase lengths, even key of compositions all got pushed to the limit for maximum effect.”

And sometimes those effects are hard on the musicians. “There is no room to become complacent,” Kim said. “The dynamic shifts are often sudden, and articulations need to be crisp and precise. Rhythmically there are things that keep us on our toes too.”

In the Fifth and Seventh symphonies, “people like the rhythm for the same reason they like rock or pop; it makes you want to move,” Tisdel said. “It is also one reason why the symphonies are hard to play. It is tiring to play the same rhythm over and over. When you lose the rhythmic drive of Beethoven, you’ve lost its essence.”

The composer himself played piano, violin and viola, but Chen enjoys his writing for the bassoon, too. “You can hear Beethoven’s mastery later this season when the MSO plays his violin concerto, which has many beautiful moments for the bassoon,” she said, “and his Symphony No. 4, which is full of challenging, delicate and intricate bassoon passages.”

Inevitably, Beethoven was a huge influence on composers who came after him. “It was like Pandora’s box had opened and now the sound possibilities were endless,” Chen said. Both she and Kim cited Brahms as a composer who wrestled with Beethoven’s legacy, and Tisdel said, “Bruckner and Mahler could not have existed without Beethoven. Schubert took Beethoven’s expanded length and rhythmic obsession even further. There are many other examples.”

Kim, who is also an active chamber musician, has performed all 16 string quartets with the Philomusica Quartet. “I would say that the late string quartets, probably only paralleled by the late piano sonatas, exceed the scope of the symphonies as they reach toward the cosmic in musical expression,” she said.

“I’m lucky that Beethoven wrote many incredible chamber works including the cello,” Tisdel said. “The five sonatas and three variation sets are all immensely satisfying to play. The six piano trios are also uniformly great. The string quartets? That’s even harder! If I had to pick one favorite piece by anyone, it might be Op. 127. I had the good fortune to play this with an outstanding group many years ago, and the memory is indelible.”

Lisa Fuller’s favorite Beethoven memory is a little different: “Listening to my Classette tape of the Emperor Piano Concerto while stargazing at Loveland Pass, Col., and pondering my Creator. Of course, that’s if you don’t count the times I pounded out the Pathetique Sonata to work out the angst of mothering a colicky baby! Beethoven has provided much to the soundtrack of my life. I’m grateful.”